Last Updated on 27 August 2024 by Cycloscope

Save the Rivers, an interview about so-called clean energy in Borneo

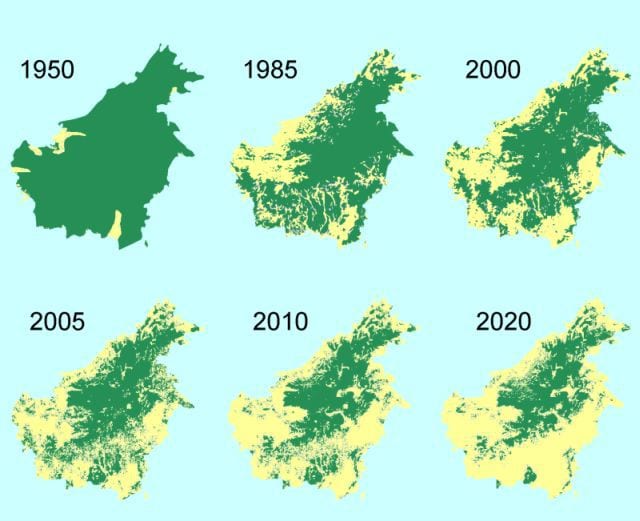

The word “Borneo” evokes myths of lush rainforests, strange and dangerous animals, and populations of fascinating costumes… all true, until some time ago.

Of the Borneo depicted in Salgari’s novels indeed very little still remains, deforestation has reached even the most remote areas. The jungle was cleared away to make way for lucrative palm oil plantations, or submerged to create reserves for the production of hydroelectric energy, the so-called “clean” energy.

While the topic of palm oil was also extensively addressed by the Western media, the issue of hydropower is still unknown to most people, though the threat it poses is not much smaller.

We decided to meet Save Rivers, an NGO based in Miri, Sarawak, one of two regions that make up the Malaysian Borneo. The association has been working for years in the defense of river ecosystems and the people who live in symbiosis with them. Not just animals and plants are in fact in danger, but entire populations, cultures, and traditions.

Check also

We meet Peter Kallang, a SAVE Rivers representative, in his office in Miri:

We are with Peter of Save Rivers, a network of people and organizations, with which we will talk about the ongoing plans to build several dams in Sarawak, Borneo, for the production of electricity and how this has caused and will cause enormous environmental damage and the forced extinction many native peoples of Borneo.

We’ll begin talking about the Bakun Dam, one of the completed projects, what can you tell us about it?

The Bakun Dam is the second dam completed. Before Bakun another one was built, in Batang Ai, completed in 1986. This project struck a thousand people who were evicted from their homes and relocated. These people made many promises, but still, many issues are unresolved, in particular, those concerning the land.

In the late 80s our then-prime minister, Mahathir Mohamad, said that the rivers are the Sarawak wealth for the production of electricity. This energy would be useful not only for Sarawak but was expected to be exported up to Peninsular Malaysia and from there to Singapore. This is the reason why the Bakun dam was designed. It was made operative in 2011 and it’s at the present moment the biggest dam in Asia outside China.

To export the energy we would need submarine cables, but because of the undeveloped technology and the large distance between Borneo and Peninsular Malaysia, the enormous costs would not be recovered. So the energy remains in Sarawak, where, however, the demand is not as high.

The Bakun dam has a capacity of 2400 MW when the maximum energy demand in Sarawak was 1,900 MW in 2010.

Our Minister for Energy at the time, Peter Chin, in fact, affirmed that Sarawak would not need any new hydroelectric power plants. But in 1997 the government decided to set the agenda to industrialize Sarawak by 2030, thus justifying the need for greater energy production.

In 2008 the project SCORE (Sarawak Corridor for Renewable Energy) was launched. The aim was to make Sarawak a sort of energy reserve not only for Malaysia (Sarawak, Sabah, and Peninsular Malaysia) but also for exports to Indonesia, Brunei, Singapore, Thailand, and so on to the entire Southeast Asia.

At least that was their dream, to achieve it they found 52 sites suitable for the construction of dams. With the construction of 20 or 30 dams, they would generate 28,000 MW, which is definitely a huge amount of energy.

“Building dams here in the tropics will generate more greenhouse effect than a normal fossil fuel power plant”

Thirty times higher than the current needs of Malaysian Borneo…

Yes, even more. So, according to this project, 20,000mw would be from hydro, 5,000 from coal which is plentiful in the Mukah region (in the center of Sarawak), and 3,000mw from solar and natural gas. The name for the Sarawak Corridor Renewable Energy, you will agree with me, is somewhat misleading. Coal is not renewable and certainly building dams here in the tropics will generate more greenhouse effect than a normal fossil fuel power plant.

Tell us why

The construction of dams implies that the forest is flooded and all these trees and vegetation under water, rotting, will produce enormous quantities of greenhouse gasses.

In addition, our climate is affected by the phenomenon called Siltation in practice is water pollution due to deforestation to make way for plantations of oil palm; the soil, debris, and waste production, no longer having a forest to “block” it ends up in the rivers. In the tropics, according to experts, the duration of a dam is on average 50 years, after which it is no longer economically viable.

After only 50 years?

Yes, precisely because of Siltation, especially here in Sarawak. If you are going to see the Bakun Dam, you will see oil palm plantations all around. Where there is still a bit of forest they are cutting down trees for logging and all that remains ends up in the rivers.

I understand, then how many people were affected by the Bakun Dam project and what was their fate? How did he change their lives and what they were given in return?

Those affected by the construction of the Bakun dam are the inhabitants of 15 villages, about 20,000 people were forced to leave their homes and were relocated to a new area, Sungai Asap (in this link the story of our visit to Sungai Asap). When the government tried to sell the idea of the dam, it said to have learned the lesson from the story of the previous dam, Batang Ai, and promised free electricity, free water, free houses, and schools for children. Everyone would have lived happily dancing and singing (laughs).

But while the people of Batang Ai got 15 hectares of arable land for each enlarged family, the Bakun folks got only three, absolutely not enough to generate an even small profit. Moreover, the housing units are not sufficient for them, families are numerous the houses are about thirty square meters, and cheap materials were used, some of the houses, in just 15 years, are beginning to deteriorate.

What about the lifestyle?

The displaced persons belong to different ethnic groups native to Borneo. The Kenyah and Kayan traditionally practiced Shifting Cultivation, an agricultural technique practiced by the peoples of the rainforest. In the dry season, they cut a small portion of the forest, they burn the soil to cultivate the land, and plant seeds in the rainy season.

After the harvest, they change the area and leave the precedent undisturbed for fifteen or twenty years. In this way the soil and the forest regenerate. We can call it itinerant agriculture. But with only 3 hectares of land, this type of farming is not viable.

Rather different for the Penan who are traditionally nomadic and have never practiced agriculture. They are hunters and have never had anything to do with money. Now they have to pay for electricity, water…

So the promise of free utilities?

Nothing is ever free, even initially they were required to pay for housing, 60,000 ringgit (13,000 euro). Even the water should be paid for, but the people opposed it because the quality is bad, really bad. You know the tea with milk, here, the color is the same.

I heard that some people have not been relocated and built houseboats in the lake dam

A portion of the relocated people has returned to the places where they once lived in search of land, but there’s nothing left, so they built houseboats. Many others moved to the city in search of a job. If you go to Sungai Asap you will see that half of the houses are empty. Only seniors are there.

There is no way to survive in this place, they have the road and electricity but as the inhabitants used to say “You cannot eat your way”, they need food.

What was rather the impact on fauna and flora, was made a study of how many and which animals would be killed.

No, it was all destroyed and no one made a sound, the only thing that matters is to build the dam and make money. Nobody is interested in plants and animals.

Just think that the species inhabiting one hectare of land in Sarawak are equivalent to all those in North America. Many we don’t even know yet, and maybe we’ll never do before they are extinct.

Who are the investors, and where do the money come from?

There are a few foreign investors, but most of the money comes from the government and is taken directly from our pension funds…

Let’s talk about the other projects, the Murum dam and that of Baram, how many people were involved, their voices will be heard this time?

The Murum dam was completed and the people relocated.

How many people? They’ve got something in return this time?

About 1,300, mostly Penan (nomadic ethnic group). In this case, the houses were built slightly better than Sunday Asap but are not the houses where these people traditionally live.

For five years, Sarawak Energy, the builder of the dam (government-owned) has promised to pay 850 ringgit per month (190 EUR), but of these 600 are deducted and converted into food that people receive every month, and only 250 are given in cash (for each family). We’re speaking of about 50 euro per month. Controlling what is given to people (rice, noodles, onions) we found that the value is not 600 but only 200 ringgit.

So the Penan, who are not farmers, wait every month for the arrival of these poor supplies. But in 5 years, when the agreement expires and they won’t get anything anymore, I’m curious to see what will happen. These people will not be able to survive.

What about Baram Dam, the project that is not yet complete?

With Save Rivers we were able to get down there and talk to the people, showing them videos of other finished projects and how’s life now for the displaced persons.

We brought people from Bakun in Baram to explain what has happened and what will happen again and we brought people from Baram to the villages where people have been relocated to show directly what it means.

The opportunity to see what could be their future created a strong resistance from the people of Baram. When Sarawak Energy went to negotiate with them, no one wanted to cooperate.

The Baram area is very wide, how many people are involved?

At least 20,000 people from 30 longhouses. But they don’t only want to build one dam in Baram, but four, only the first will involve 20,000 people. If it’s built 39,000ha of the forest will be flooded.

Baram, maybe because I was born there, it is a beautiful place, one of the most beautiful in Sarawak, rich in rivers and waterfalls. It would be a huge loss.

Watch this documentary about Bakun Dam, before the resettlement

Liked this article, do you want to support the Borneo people’s cause? Share it!

Have thoughts about it? Comment!

Go to the 2nd chapter of the reportage:

Sungai Asap, the Bakun dam resettlement area – people on the verge of extinction

Our previous adventures in Borneo

pt1: from Kota Kinabalu to Tenom, crossing the Crocker range

pt2: Jungle Train, from Tenom to Beaufort

pt3: crossing Brunei by bicycle

pt4: around Miri, Lambir Hills and Logan Bunut national parks and Tusan Beach

pt5: the caves of Niah National Park

pt6: from Belaga to Kuching by boat

pt7: Kuching and Bako National Park

pt8: Rafflesia in Gunung Gading National Park

pt9: Overland Border crossing from Sarawak into Kalimantan, the secret Aruk border

pt10: Sambas, the wooden Venice of Indonesian Borneo

Reportages

Chap Go Meh in Singkawang:

piercing yourself with swords to please your Gods

Hydroelectric devastation in Borneo

part 1: Interview with SaveRivers (you are here)

part2: a visit to Sungai Asap

here are some general hints to budget travel in Borneo (by bicycle or not)